...what we will be

has not yet been revealed.

- First John 3:2

ONE DAY, IN THE FINAL DECADE of

the last century, I found myself brooding

over the futility of the alien life I’d

wandered into. I shut off my telephone,

closed my office door. My eyes fell upon

this new device that squatted on a

writing desk over near the window.

I pressed a switch and the screen shone

bright and pure. Not a virgin sheet of

foolscap, but close enough.

I found myself writing—not advertising copy, but a story.

A true story that had haunted me for much of my life since the

first hint of it, when I was a boy.

The rest of that day I dwelt vicariously in an era before I was

born. The result was “Tracks and Ties.”—soon to be christened Chapter One.

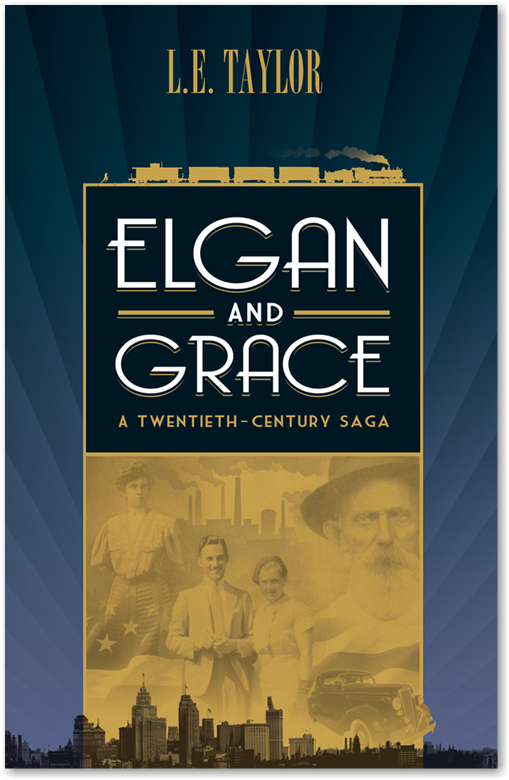

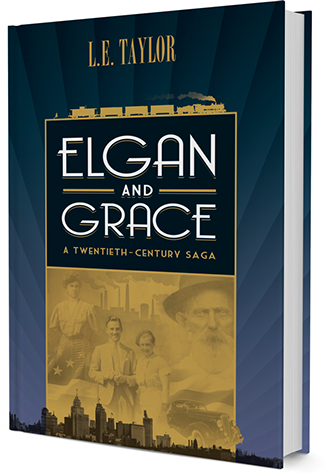

Elgan and Grace, A Twentieth Century Saga became a

decade-long labor. It was written for you.

Taken together, almost in any sequence, its fragments are scenes remembered—poignant and jarring, spiritual and profane. They bear witness to virtue and vice, hope and heartbreak, to passion and folly and the ardent promise of redemption. Some arrive for your judgment just as they happened, some as they might have happened. A few are recalled as they never were. Like every story, the parts are not all facts; they are not all faith.

Yet, the tale, however it congeals in your care,

is most certainly true.

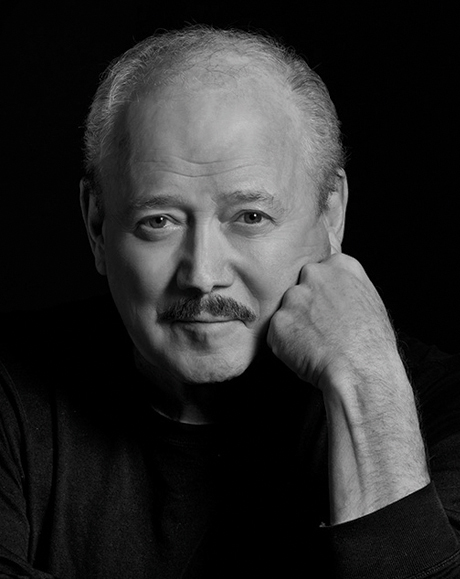

L. E. Taylor is a product of the 1930s and ’40s, the first son of a hybrid Middle American family—itself a resilient mix of Scots-Irish Kentucky coal miners and poor German immigrants. The novel comes together at the social and economic battleground of an age: Detroit.

Historically authentic settings and mores rekindle the past: backwoods Kentucky, a booming young Detroit, anti-German hostility during The Great War, whiskey-running and speakeasies, twists of fortune after The Crash, the Machiavellian inner sanctums of the world's largest industry, the World War II American home front—and finally, sea-changes in society and in private lives that accompanied Post-War normalcy.

Caution: The book is based upon oral history, family lore, and first hand memory. It is an adventure, a spiritual journey… and to delicate 21st century sensibilities, politically incorrect to a fault. So be warned.

The story is written exactly as people behaved, spoke, and lived. To change one word to accommodate 21st century fads would be irresponsible, factually and artistically. And it would be insulting to the memory of those—with all their flaws—who’ve preceded us.

-

From Chalk Talk (page 9)

-

From That Woman (page 16)

-

From False Start (page 22)

-

Also from False Start (page 24)

-

From Going to Eloise (page 32)

-

From Papa's Girl (page 40)

-

Also from Papa's Girl (page 43)

-

From Owensboro Game (page 83)

-

A letter home, from Curse of the Radio People (page 205)

-

From Old Kenturcky Home. Far Away (page 213)

-

From A New Man (page 247)

-

From Old Time's Sake (page 364)

Excerpts

Ω